Digital Objects in a Circuit of Meaning

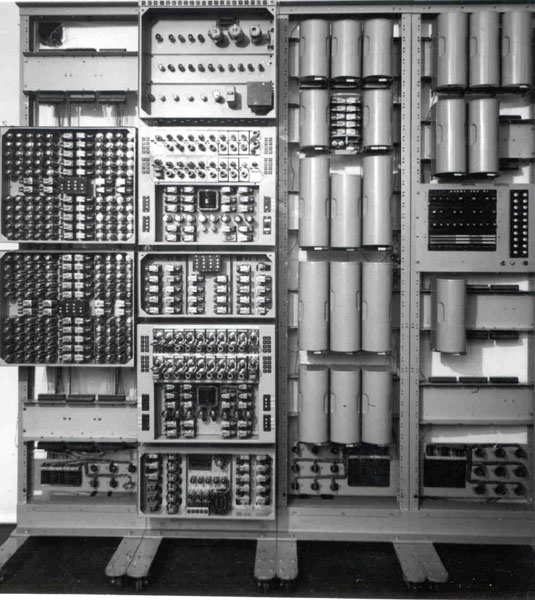

The Harwell Dekatron computer, also known as the Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computing from Harwell (WITCH), is an early British relay-based computer of the 1950s, now part of The National Museum of Computing’s exhibition.

If the preservation and exhibition of historical objects is one of the key activities and mandates of many museums, curatorial practices constantly challenge what we mean with the word “object.” The research group I am leading within the Circuits of Practice project, named the Circuit 2 “Objects,” takes up the case of digital objects to interrogate how our partner museums are shifting the boundaries of museum practice and, in the process, improving our understanding of hardware and software artefacts as historical objects.

Three museum partners were involved in our Circuit: The National Museum of Computing in Bletchley, UK, the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, Italy, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK. For each partner, we selected an object or a set of objects from the museum’s collection that served as case studies to interrogate the role of digital objects in constructing histories of computing within museum environments. Drawing from theoretical and methodological resources in fields including anthropology, media studies, and museum studies, we conducted seven dedicated workshops that mobilized action research methods and design thinking methodologies.

Taking up a research agenda, one should always be prepared to reformulate the problems and questions that were considered at the outset. This was also the case of the explorations we conducted within our Circuit. Although our starting point had been to ask what we meant when we were talking about “digital objects,” throughout our research it became clear that no single answer could be provided to this question. In fact, the definitions, meanings and values of digital objects are never a given but emerge through and within a network of relations between the objects, other items and trajectories in the collection, the curators and practitioners, the institutions, and the visitors of the museum. The digital objects under examination, in this sense, are revealed to be not singular but rather plural entities, whose values emerge in relationship to the particular spatial and organisational contexts in which they were framed, and the specific social, discursive, and affective meanings that people, including curators, volunteers, visitors, project onto them.

The practice-based research conducted with our partners provided not just insight into museum practice but also, more broadly, an entry point into the multidimensional nature of digital objects. Much as digital objects throughout their social “lives” become repositories of multiple social uses, meanings, and exchanges (as they were created, used, circulated, and eventually discarded outside the museum), so these objects also establish a relational and iterative social “circuit of meaning” within the museum environment.

Importantly, the three cases enabled us to take into account the different perspectives through which each institution approaches digital objects and more broadly histories of computing. At The National Museum of Computing, the meaning of the Harwell Dekatron developed through the intellectual and affective work of the volunteers and as an effect of a wider “community of machines” – i.e. the discursive and material relations between all the different objects in the collection. At the National Museum Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci, the case study showed that the object’s values depended not only on the objects themselves but also on their contextualization in different spaces of the museum. At the Victoria & Albert Museum, new practices on how to curate software developed not only and not predominantly by posing the question of “what is software,” but rather by interrogating what software means from the particular point of view of a design history museum.

The museum emerges, from this perspective, as a context in which meanings, uses, and definitions of these objects are self-reflectively renegotiated, and a laboratory through which insights into the relational circumstances that shape the very nature of digital objects can become manifest and further understood.